Min Nan

| Southern Min | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 閩南語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 闽南语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southern Min | ||

|---|---|---|

| 閩南語 / 闽南语 / Bân-lâm-gú | ||

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Southern Fujian province; the Chaozhou-Shantou (Chaoshan) area and Leizhou Peninsula in Guangdong province; extreme south of Zhejiang province; much of Hainan province(if Hainanese or Qiong Wen is included); and most of Taiwan; | |

| Total speakers | 49 million | |

| Ranking | 21 (if Qiong Wen is included) | |

| Language family | Sino-Tibetan

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | None (Legislative bills have been proposed for Taiwanese (Amoy Southern Min) to be one of the 'national languages' in Taiwan); one of the statutory languages for public transport announcements in the ROC [1] | |

| Regulated by | None (The Republic of China Ministry of Education and some NGOs are influential in Taiwan) | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | zh | |

| ISO 639-2 | chi (B) | zho (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | nan | |

| Linguasphere | ||

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

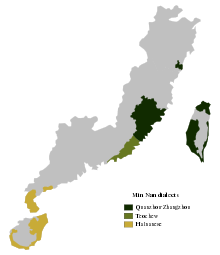

The Southern Min languages, or Min Nan (simplified Chinese: 闽南语; traditional Chinese: 閩南語; pinyin: Mǐnnán yǔ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Bân-lâm-gí/Bân-lâm-gú), ("Southern Fujian" language) is a family of Chinese languages which are spoken in southern Fujian and its neighbouring regions, Taiwan, and by descendants of emigrants from these areas in diaspora.

In common parlance, Southern Min usually refers to Hokkien, in particular the Amoy and Taiwanese. Amoy and Taiwanese are both combinations of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou speech. The Southern Min family also includes Teochew and Hainanese. Teochew has limited mutual intelligibility with the Amoy. However, Hainanese is generally not considered to be mutually intelligible with any other Southern Min variants.

Southern Min forms part of the Min language group, alongside several other divisions. The Min languages/dialects are part of the Chinese language group, itself a member of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Southern Min is not mutually intelligible with Eastern Min, Cantonese, or Mandarin. As with other varieties of Chinese, there is a political dispute as to whether the Southern Min language should be called a language or a dialect.

Contents |

Geographic distribution

Southern Min is spoken in the southern part of Fujian province, three southeastern counties of Zhejiang province, the Zhoushan archipelago off Ningbo in Zhejiang, and the eastern part of Guangdong province (Chaoshan region). The Qiong Wen variant spoken in the Leizhou peninsula of Guangdong province, as well as Hainan province, which is not mutually intelligible with standard Minnan or Teochew, is classified in some schemes as part of Southern Min and in other schemes as separate.

A form of Southern Min akin to that spoken in southern Fujian is also spoken in Taiwan, where it has the native name of Tâi-oân-oē or Hō-ló-oē. The (sub)ethnic group for which Southern Min is considered a native language is known as the Holo (Hō-ló) or Hoklo, the main ethnicity of Taiwan. The correspondence between language and ethnicity is generally true though not absolute, as some Hoklo have very limited proficiency in Southern Min while some non-Hoklos speak Southern Min fluently.

There are many Southern Min speakers also among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. Many ethnic Chinese emigrants to the region were Hoklo from southern Fujian, and brought the language to what is now Indonesia (the former Dutch East Indies) and present day Malaysia and Singapore (formerly Malaya, Burma, and the British Straits Settlements). In general, Southern Min from southern Fujian is known as Hokkien, Hokkienese, Fukien or Fookien in Southeast Asia, and is very much like Taiwanese. Many Southeast Asian ethnic Chinese also originated in the Chaoshan region of Guangdong province and speak Teochew, the variant of Southern Min from that region. Southern Min is reportedly the native language of up to 98.5% of the community of ethnic Chinese in the Philippines, among whom it is also known as Lan-nang or Lán-lâng-oē ("Our people’s language"). Southern Min speakers form the majority of Chinese in Singapore with the largest being Hoklos and the second largest being the Teochews.

Classification

Southern Fujian is home to three main Amoy dialects. They are known by the geographic locations to which they correspond (listed north to south):

- Quanzhou

- Chinchew

- 泉州

- Amoy

- 廈門

- Zhangzhou

- Changchew

- 漳州

As Xiamen is the principal city of southern Fujian, the Xiamen dialect is considered the most important, or even prestige dialect. The Xiamen dialect is a hybrid of the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects. The Xiamen dialect (also known as the Amoy dialect) has played an influential role in history, especially in the relations of Western nations with China, and was one of the most frequently learned of all Chinese languages/dialects by Westerners during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century.

The variants of Southern Min spoken in Zhejiang province are most akin to that spoken in Quanzhou. The variants spoken in Taiwan are similar to the three Fujian variants, and are collectively known as Taiwanese. Taiwanese is used by a majority of the population and is quite important from a socio-political and cultural perspective, forming the second most important, if not the more influential pole of the language due to the popularity of Taiwanese Hokkien media. Those Southern Min variants that are collectively known as "Hokkien" in Southeast Asia also originate from these variants. The variants of Southern Min in the Chaoshan region of eastern Guangdong province are collectively known as Teochew or Chaozhou. Teochew is of great importance in the Southeast Asian Chinese diaspora, particularly in Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Sumatra and West Kalimantan.

The Southern Min language variant spoken around Shanwei and Haifeng differs markedly from Teochew and may represent a later migration from Zhangzhou. Linguistically, it lies between Teochew and Amoy. In southwestern Fujian, the local variants in Longyan and Zhangping form a separate division of Min Nan on their own. Among ethnic Chinese inhabitants of Penang, Malaysia and Medan, Indonesia, a distinct form of Zhangzhou (Changchew) Hokkien has developed. In Penang, it is called Penang Hokkien while across the Malacca Strait in Medan, an almost identical variant is known as Medan Hokkien.

Cultural and political role

Jean DeBernardi of the University of Alberta stated that Min Nan (閩南話), is a Sinitic language with more than 38 millions users, which is 4% of the 1 billion speakers of Sinitic languages. The Min Nan user are in parts of Fujian province, Northeastern Guangdong, Hainan, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, Thailand,Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and the Philippines. In addition to its high social value as a marker of in-group status among the various communities, it has acquired an additional political value in Taiwan, representing the aspirations of the Taiwanese independence movement in the face of fears of reunification with Mainland China.[1]

Jean DeBernardi considered calling Min Nan a ‘dialect’ "is a misnomer", as the languages of China are as diverse as Romance languages. While Northern China is claimed to be relatively homogeneous linguistically (although Jerry Norman observes that “many varieties of Mandarin in Shanxi and the Northwest are totally incomprehensible to a Beijing speaker”), Southern China has six major ‘dialect’ groups, which are mutually incomprehensible tongues.

Since the Guomindang's 1945 defeat in Mainland China and its subsequent retreat to Taiwan, Mandarin has been encouraged at the expense of Taiwanese. Min Nan, though spoken by an estimated 80% of the Taiwan population, has been regarded as "a substandard language with no grammar and no written form, inadequate and unsuitable for cultivated discussion”.

Many older Min Nan speakers in both Tainan and Xiamen expressed the view that Min Nan was superior to Mandarin, which was viewed as a recently invented language lacking the historical roots of Southern Min... the promotion of Mandarin in both Taiwan and the PRC was a means of promoting the political dominance of Northern China, and speculated that politicians feared the strength of Min Nan people, who... had been economically successful everywhere they have lived and worked.—[2]

Phonology

The Southern Min language has one of the most diverse phonologies of Chinese variants, with more consonants than standard Mandarin or Cantonese. Vowels, on the other hand, are more or less similar to those of Standard Mandarin. In general, Southern Min dialects have five to six tones, and tone sandhi is extensive. There are minor variations within Hokkien, but the Teochew system differs significantly.

Varieties

Xiamen speech is a hybrid of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou speech. Taiwanese is also a hybrid of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou speech. Taiwanese in northern Taiwan tends to be based on Quanzhou speech, whereas the Taiwanese spoken in southern Taiwan tends to be based on Zhangzhou speech. There are minor variations in pronunciation and vocabulary between Quanzhou and Zhangzhou speech. The grammar is basically the same. Additionally, Taiwanese includes several dozen loanwords from Japanese. In contrast, Teochew speech is significantly different from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou speech in both pronunciation and vocabulary.

Vowel shifts

The following table provides words that illustrate some of the more commonly seen vowel shifts. Characters with same vowel are shown in parentheses.

| English | Chinese character | Accent | Pe̍h-ōe-jī | IPA | Teochew Peng'Im |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| two | 二 | Quanzhou, Taipei | lī | li˧ | no6, ri6 (nõ˧˥, zi˧˥)[3] |

| Xiamen, Zhangzhou, Tainan | jī | dzi˧ | |||

| sick | 病 (生) | Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taipei | pīⁿ | pĩ˧ | bên7 (pẽ˩) |

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | pēⁿ | pẽ˧ | |||

| egg | 卵 (遠) | Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taiwan | nn̄g | nŋ˧ | neng6 (nŋ˧˥) |

| Zhangzhou | nūi | nui˧ | |||

| chopsticks | 箸 (豬) | Quanzhou | tīr | tɯ˧ | de7 (tɤ˩) |

| Xiamen | tū | tu˧ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Taiwan | tī | ti˧ | |||

| shoes | 鞋 (街) | ||||

| Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taipei | uê | ue˧˥ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | ê | e˧˥ | |||

| leather | 皮 (未) | Quanzhou | phêr | pʰə˨˩ | puê5 (pʰue˩) |

| Xiamen, Taipei | phê | pʰe˨˩ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | phôe | pʰue˧˧ | |||

| chicken | 雞 (細) | Quanzhou, Xiamen | koe | kue | ? |

| Zhangzhou, Taiwan | ke | ke | |||

| fire | 火 (過) | Quanzhou | hə | hə | ? |

| Xiamen | hé | he | |||

| Zhangzhou, Taiwan | hoé | hue | |||

| thought | 思 | Quanzhou | sy | sɯ | ? |

| Xiamen, Taipei | su | su | |||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | si | si |

Mutual intelligibility

Spoken mutual intelligibility

Quanzhou speech, Xiamen (Amoy) speech, Zhangzhou speech and Taiwanese are mutually intelligible. Chaozhou (Teochew) speech and Amoy speech are 84.3% phonetically similar[4] and 33.8% lexically similar,[5] whereas Mandarin and Amoy Min Nan are 62% phonetically similar[4] and 15.1% lexically similar.[5] In comparison, German and English are 60% lexically similar.[6] In other words, Chao-Shan, including Swatow (both of which are variants of Teochew), has very low intelligibility with Amoy,[7] and Amoy and Teochew are not mutually intelligible with Mandarin. However, many Amoy and Teochew speakers speak Mandarin as a second or third language.

Written mutual intelligibility

Southern Min dialects lack a standardized written language. Southern Min speakers are taught how to read Standard Mandarin in school. As a result, there has not been an urgent need to develop a writing system. In recent years, an increasing number of Southern Min Language speakers have become interested in developing a standard writing system (either by using Chinese Characters, or using Romanized script).

See also

- Languages of China

- Languages of Taiwan

- Malaysian Chinese

- Chinese in Singapore

- Amoy Min Nan Swadesh list

Related languages

- Penang Hokkien

- Southern Malaysia and Singapore Hokkien

- Lan-nang (Filipino dialect of Min Nan)

- Taiwanese Hokkien

- Fuzhou dialect (Min Dong branch)

- Hakka language

References

- ↑ Jean DeBernardi (August 1991). "Linguistic Nationalism: The Case of Southern Min". Sino-Platonic Papers. http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp025_taiwanese.html#n1. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ Jean DeBernardi (August 1991). "Linguistic Nationalism: The Case of Southern Min". Sino-Platonic Papers. http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp025_taiwanese.html#n1. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ for Teochew Peng'Im on the word 'two', ri6 can also be written as dzi6.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 glossika Southern Min Language phonetics

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 glossika Southern Min Language

- ↑ Ethnologue: German

- ↑ Ethnologue: Min Nan

Further reading

- Branner, David Prager (2000). Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology — the Classification of Miin and Hakka. Trends in Linguistics series, no. 123. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 31-101-5831-0.

- Chung, R.-f (196). The segmental phonology of Southern Min in Taiwan. Taipei: Crane Pub. Co. ISBN 95-794-6346-8.

- DeBernardi, J. E (1991). "Linguistic nationalism--the case of Southern Min ". Dept. of Oriental Studies, University of Pennsylvania..

External links

- 當代泉州音字彙, a dictionary of Quanzhou speech

- 台語-華語線頂辭典, Taiwanese-Mandarin on-line dictionary (Min-nan)(Chinese)

- 台語線頂字典, Taiwanese Hokkien Han Character online dictionary.

- 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典, Taiwanese Hokkien Commonly-used Words Dictionary by Ministry of Education, Republic of China (Taiwan).

- 臺灣本土語言互譯及語音合成系統, Taiwanese-Hakka-Mandarin on-line conversion

- Voyager - Spacecraft - Golden Record - Greetings From Earth - Amoy The voyager clip says: Thài-khong pêng-iú, lín-hó. Lín chia̍h-pá—bē? Ū-êng, to̍h lâi gún chia chē—ô·! 太空朋友,恁好。恁食飽未?有閒著來阮遮坐哦!

- 台語詞典 Taiwanese-English-Mandarin Dictionary

- How to Forget Your Mother Tongue and Remember Your National Language by Victor H. Mair University of Pennsylvania

- wikt:Appendix:Sino-Tibetan Swadesh lists

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||